May 2015 Issue number two/The Memory of Taste

When we eat something remarkable all of our senses are engaged, when that taste occurs in a distinct place and time of our lives the memory of that food and the feelings it conjures becomes imprinted on our DNA. It is a universal phenomenon yet it is unique to every human being.

This second issue of Scroll explores the extraordinary poetry and visceral power of the memory of taste. Ask anyone to recall their most vivid food recollection and guaranteed it will provide insight into who they are and where they come from. So on that note, we have asked a collection of the most intriguing people we know, from all over the world and from various walks of life, to share their most vivid food memory. We gave no constraints but curiously each writer recalled their childhood and each a simple taste sensation.

As a food writer, my bread and butter is recalling in detail what I ate and so it was a delight to ask others to do the same. Skye and I are both so honoured that each of these individuals took the time to share with us a memory that has stayed with them and become part of their extraordinary lives.

Enjoy.

David Prior

Gilbert Pilgram – Chef and co-owner of Zuni Café, San Francisco

As gifted a raconteur as he is restaurateur, in recent years the charismatic co-owner of Zuni Café has admirably steered the San Franciso institution through the keenly felt passing of its beloved chef Judy Rodgers with his optimism, wicked humor and singular style. They are traits that he was already developing as a boy in the markets of Mexico City…

Lilia, my grandmother, was an extraordinary cook. My passion for cooking came from her. She was also an avid shopper. My passion for shopping came from her too.

I grew up in Mexico City. In the mid-’60s, farmers’ markets sprouted all over the city. Looking back, this was clearly a homegrown response to the supermercados.My grandmother could not accept the new order. Supermarkets were not her thing. I remember being a bit embarrassed that we would shop at the tianguis, as the farmers’ markets are called in Mexico. Once I was of a porter’s age, she would always bring me to carry the bolsas del mercado. Lilia knew all the vendors by name and that every farmer had a specialty – nopales from a lady on Fridays, chickens from a handsome butcher in Coyoacán, and bolillos after 4.30pm. This is how I fell in love with mangoes – still my favourite fruit.

Americans love peaches because they have not had a good mango. Once you do, you are hooked. Mangoes introduced me to the seasons. I could only get mangoes in spring and summer. At the tianguis, you could buy them skewered on a wooden stick and topped with salt, chilli and freshly squeezed lime juice.

Mango farmers had different specialities. Manila and petacon being the predominant varieties. I liked petacon. Being able to say its name made me feel grown-up. Petacon is slang for big buttocks in Mexican Spanish. It gave me giggly pleasure to be able to order a mango petacon. I could say that forbidden word without a reprimand and be rewarded with a big mango that I could eat – slobbering it all over myself – and then gladly carry 10 more kilos home to enjoy. Lilia caught on to this. She could shop to her heart’s content and load her personal Sherpa with all she wanted, as long as she bribed me with a juicy, big-ass mango!

Anjelica Huston – Oscar winning actress, fashion model-muse and author

When we talk about extraordinary lives it almost goes without saying that few have lived a more remarkable one than Anjelica. Instantly recognizable the world over, she has lived her entire life under the pressure of the public spotlight and in the company of outsized personalities yet she has always remained a total original. Here the oscar winning actress and muse to many celebrates the bounty of her Irish upbringing.

In Clarinbridge, a small coastal village on the west coast of Ireland, some 20 kilometers from where I grew up, the oysters were picked from the sea outside the back door of Paddy Burke’s bar and lounge. Beginning in September, any month with an ‘r’ was open oyster season, and whenever Dad would come home for vacations from his work abroad as a film director, there were excursions to Paddy Burke’s, which lasted well throughout April. Visitors and houseguests, alighting from several cars and station wagons, entered through a red door on the bayside of the old bridge, where the ice-cold Atlantic lapped at the limestone, the limpets sticking fast to the rocks buried in brown seaweed.

When you entered Paddy Burke’s, the light shifted to darkness and amber under a low ceiling. A red curtain that divided the bar from the kitchen was drawn to one side, as Paddy Burke himself emerged from the background into the lounge, laughing and telling jokes and flattering my father. Then my brother Tony and I would go to the bar to watch Johnny shuck oysters. He was supposed to be the fastest oyster shucker in the world, and had won trophies in America. But I was six years old and didn’t really understand oysters. They were supposed to be alive, and at Paddy Burke’s, the oysters actually wriggled when you squeezed lemon on them, which worried me no end.

But what was best of all at Paddy Burke’s was the smoked salmon; fresh from Lough Corrib, deep pink and sliced like tissue paper, with capers on sliced soda bread made with whole wheat and buttermilk, lightly toasted and dripping with fresh Irish-creamery butter.

Robert Fox – Legendary British theatre and film producer

Bob is the very best of eating companions. Not only does he order well, he’s also generous conversationalist who is content to let others tell their stories. That shouldn’t come as a surprise having helped bring to life some of the greatest storytelling of our age including many of David Hare’s plays and films The Hours, Notes on a Scandal and Iris. Here he tells the tale of his favourite jam roly-poly boiled pudding.

My family were lucky in that we had two wonderful sisters who worked for us – Alice, who was our cook, and Edie, her sister, who did all our washing and mending and the such. But it was Edie who made my favourite jam roly-poly boiled pudding better than Alice. I remember them both being very competitive as to who made it best, but when it came to the crunch, it was Edie. When she pulled the pudding out of the boiling pan – in its white cloth, tied at both ends with string – it would roll out with none of the suet sticking to the side. I would be there with my bowl and spoon ready for the first slice, which I would cover with fresh cream from the dairy in our village, owned by Mr Gubbins. Heaven.

David Pocock – Rugby Union player, former Captain of the Australian Wallabies and activist

David Pocock is full of surprises, a star rugby player who is also an unlikely champion of the environment and social justice. Not content to revel in sporting adulation, Pocock uses his powerful platform to upend stereotypes and provoke discussion in the most articulate, steady and thoughtful way. Here he also reveals a talent for food writing, illuminating below the diversity of mangoes in his childhood home of Zimbabwe.

November in Zimbabwe and the first mangoes of the season on my grandfather’s nearby citrus farm were always greeted with a lot of excitement. We farmed about five hours away on a mixed-crop farm, but were often at my grandfather’s for holidays, or they would send boxes of mangoes and other citrus to us.

The first mangoes to ripen were the Haden – its deep-yellow with red-crimson blush signalling the start of mango season. Then the sort-of-Haden-but-not-quite-as-nice Zill and Tommy Atkins would start to ripen in December. Then, in January, when we were back on the farm and back at school, boxes of huge, green-turning-yellow Kent would arrive. The Kent always looked like too much until you started eating it and then it definitely was not. Looking back, it was a great lesson in seasonality. By spring we couldn’t wait for mangoes, and very specifically we couldn’t wait for Hadens.

As a 10-year-old, with the vast array of mangoes that were a part of my life – growing, picking, processing, boxing – I knew a mango wasn’t just a mango. Each variety seemed so different, so unique, so special. Though you’d never eat a Tommy Atkins if there were any other mangoes around, in its favour, it stored for longer than the others, so was better to take home from the citrus farm for the weeks ahead.

The taste of looming summer will now forever be marked for me by the memory of those first tastes of the almighty Haden – and no other mango will ever quite hit the spot.

Mary McCartney – Photographer

A gifted photographer with an eye for the beauty of the everyday, Mary McCartney inherited more than just her talent from her famous parents Paul and Linda, she also adopted a food philosophy that was before its time. From a family of vegetarians, here she shares the promise of a decadent cheese soufflé rising in the oven and almost ready to be shared.

If my mum and I could sit down now and say what was our favourite dish of all time, it would almost certainly be a cheese soufflé. She used to make it for me, I used to make it for her. It’s super impressive with massive taste and satisfaction factor but, actually, is far simpler to make than you would ever think. To this day, when I look through the oven door, hoping that the soufflé is doing what I want it to do, there is always a smile on my face as those memories of my mum come flooding back.

Jane Scotter – Author and co-founder of biodynamic farm Fern Verrow

Those familiar with the food of Spring are also familiar with the produce of the pioneering biodynamic farmer, Jane Scotter. She coaxes the very best of the English growing seasons on her farm Fern Verrow for the kitchen to work with each day. Here she reflects on a red pan that has travelled with her through life and its many meals.

There is a red, heavy-based pan in my kitchen. I use it nearly every day. It is older than I am. It is the pan that my parents always took on our annual family camping holidays through France and Italy. My father and mother loved good food, not only to eat, but as a hobby. We would shop at markets every day. I remember staring at the women at the stalls, in their colourful Provençal tabliers, their weather-beaten faces reflecting the tales of their toil. The vegetables and fruit glowed with vigour and true quality. With heavy bags we returned to our campsite and cooked our lunch and supper in the red pan.

I know what a fresh courgette should look like, and from the gloss and smell of its skin, I know what it will taste like. The memories of those markets, the people selling their food those 40-plus years ago, that is me now! I am your contemporary peasant farmer. The red pan in my kitchen is a reminder of what I am striving to achieve in my growing, in partnership with my farm, the soil and the elements.

Solange Azagury-Partridge – Jeweller

As vibrant, vivid and worldly as her idiosyncratic jewellery, the celebrated designer recalls her Moroccan heritage, the visceral fragrance of cooked orange and quite literally growing up in the kitchen.

My grandmother came to live with us when I was a little girl. We only had two bedrooms, so my father built me a tiny room in the corner of the kitchen. It was big enough for my bed and not much else. And I loved it. There was a little window that overlooked the top of the fridge and the kitchen sink.

My grandmother, who I was named after and who I loved more than anyone, was always cooking.

I used to love it when she made confit oranges – a real Moroccan speciality and something we always had at Passover. We still do. I would help her scrape and scour the oranges – through my window, of course – and as I got older she let me cut the orange sections. We’d fill the pan with water, pour in the bags of sugar and the cinnamon sticks, and start boiling it all up. She’d hold me up and let me stir the pot. It would take hours to reduce and caramelise.

Finally, we’d take the oranges out and flatten them onto a plate. Once they’d cooled down, she would cut me the first piece. Sometimes we’d dip them in chocolate. Also, she was deaf and used to call me Zorange. So oranges, the smell and flavour, fresh or confit, are inextricably linked to my kind and beautiful grandma.

Skye Gyngell – Chef and owner of Spring

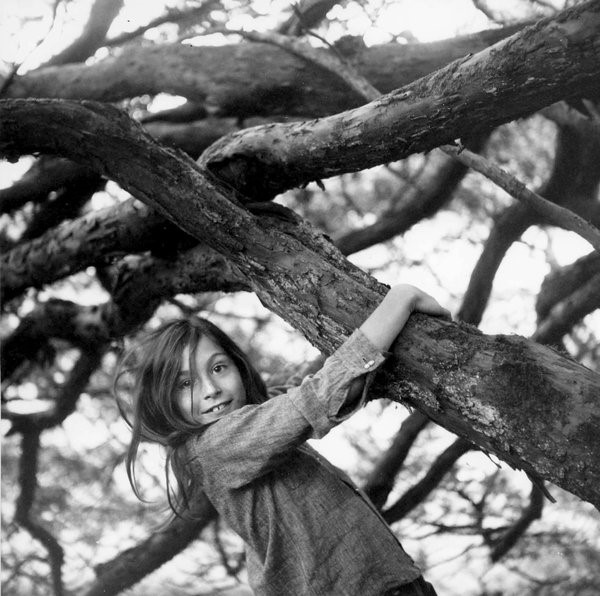

Those that know Skye and her cooking know that it is layered with the experiences of her life. In the composition of her food, Skye’s rule breaking ‘Australianess’ is never far from the surface, so too the influences she has taken from time in Italy and France and then of course her total embrace of England and its produce. Skye remembers the abundance of her grandparent’s tree and her subsequent lifelong pursuit of the mercurial mulberry.

My grandparents lived in a pale-grey weatherboard house in Hunters Hill, Sydney. The front of the house facing the street always felt gloomy, like most of the rooms inside the small home, where my father was raised. The back of the house, in stark contrast, with its large, scruffy lawn, was always bathed in light and warm sunshine. There was a big verandah encased in a fly screen that housed an old cane sofa and a couple of tatty armchairs – the part of the house I remember most vividly – where we would sit with our grandparents, drinking lemonade, when we came to visit. I loved both my grandparents, but my grandmother was rather stern and imperious, with a large beak for a nose and delusions of grandeur. I was always slightly wary of her. My grandfather, in contrast, was small, soft, quiet, and known as papa Gyngell. As children, we loved spending time with him in the garden.

At the end of the garden, by the old garage, was a large and very old mulberry tree. During the summer months, when the tree was heavy and laden with fruit – the grass black underneath its feet – we used to collect the ripe, plump, inky fruit and eat them in handfuls, sitting beneath its boughs. In the winter, we kept silkworms in shoeboxes studded with holes, and fed them mulberry leaves. That mulberry tree is probably one of my most vivid memories of my grandparents’ place. That and Sunday-night supper, which was always the same: a leg of lamb and roasted pumpkin over cooked peas, and a pavlova to finish, smothered in fresh passionfruit, achingly sweet and sharp at the same time.

Over the years, more memories of mulberries have been added too. Picking them from the top of a friend’s tree one summer’s evening, with Rose Gray swinging from the very top of a ladder. They completed perfectly a simple meal of clams with courgettes and wild fennel leaves – a very happy night surrounded by good friends and happy children. Or the tree we planted ceremoniously one year at Petersham Nurseries with great excitement and hope for the ice-cream that we dreamed of making, only to discover that we had bought the variety that didn’t bear fruit!!

Each year, I still look forward to the arrival of mulberries, which are almost impossible to buy from any supplier, as they are too delicate to be purchased commercially. I must seek out a generous friend in order to get any supply at all – often meagre – but find them I must, for I am inextricably drawn to them, their flavour so bound up in memories of happy days past!