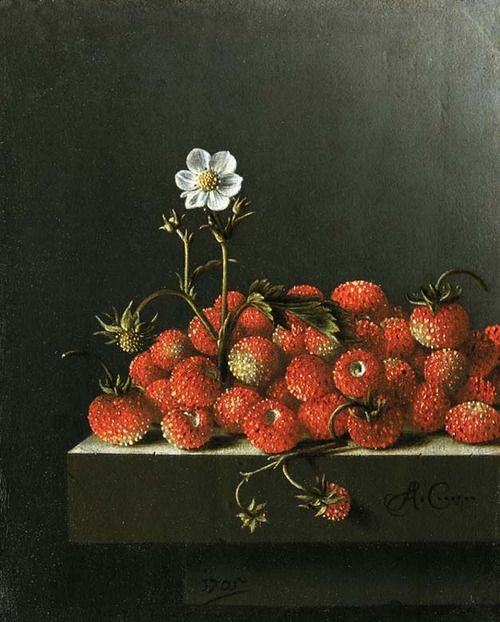

March 2015 Issue number one/The Art of Eating

Welcome to Scroll – a monthly missive from the world of Spring, written by David Prior, my friend and now my collaborator. David and I met at the first Ballymaloe Literary Festival several years ago. Soon after he wrote a number of magazine and newspaper pieces about the long road that led to the opening of the restaurant and I immediately loved and admired his taste and strong voice.

However, in the time that we have known each other, we have realised that we share more than just having both grown up in Australia. (Although it must be said that this is an important bond, swooning as we do in unison, ‘Mangoes at Christmas!’) More than that, we both share a vision; one that sees food as central to our culture and identity, and the issues that surround its production and consumption as being vital to the planet’s future.

Put simply, we believe that food matters matter. It is our belief that chefs and restaurateurs, as custodians of produce have an opportunity, perhaps even a responsibility, to feed people food and ideas. In opening Spring, my greatest hope is that the restaurant’s world might extend beyond the walls of our home at Somerset House. That there might be a way to inspire, delight, fascinate and nourish inside the dining room and out.

As we have now arrived in spring, our namesake season, we thought it fitting to launch Scroll as a first step towards sharing our ideas, loves and philosophy with you. Given our neighbours at Somerset House are galleries, arts companies and theatres, we thought it apt that the first issue explores the rarely considered role of food in a cultural institution. I hope you enjoy Scroll as much as David and I enjoy dreaming it up each month.

Skye

The Art of Eating

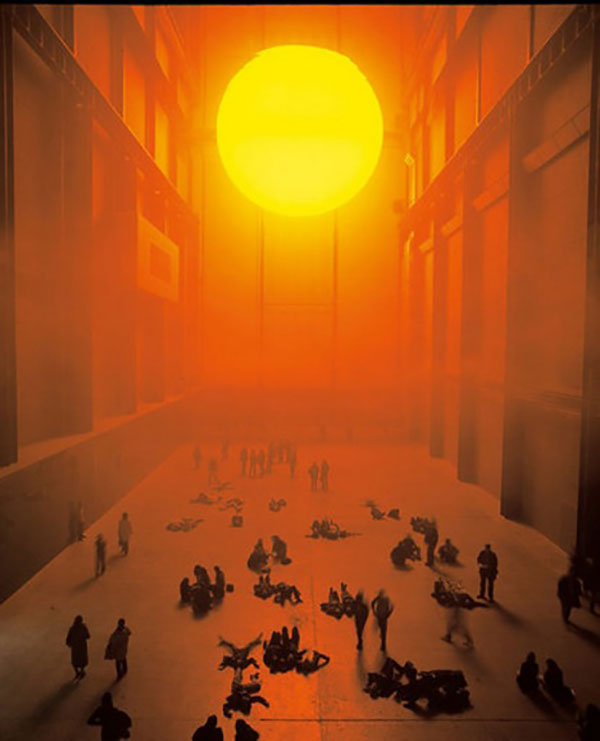

‘Cultural institutions are sites of incredible freedom in our society. They offer one of the few places where we can come together and disagree. Similarly, the cooking and effort put into making food is a gesture of generosity and hospitality; it amplifies social relations – intimate as well as global. We should think of the food that we enjoy in a cultural institution with the same attention that we think of the great works of art within its halls.’

Olafur Eliasson

Each day in the Berlin studio of the Danish-Icelandic artist Olafur Eliasson, his entire team of 90 artists, architects, craftsmen and art historians sit down to a generous shared lunch. Everything is made from scratch and in-house, and the long table where the group sits takes pride of place in the centre of the space. The buzz of the open kitchen integrates seamlessly into the hum of life at the studio, and the cooks’ work is almost interchangeable with the artists’.

The daily meal at Studio Eliasson has become more than just a moment to eat; over time evolving into a forum where ideas are discussed, advanced and subsequently brought to life. The lunch and the rituals that surround it are fuel to their creative fire. Like artists across many disciplines, Eliasson understands that the act of eating together is a powerful expression of culture and connection. However, somewhat ironically, his holistic approach to food is rarely emulated in the institutions where his dramatic and life-affirming works are installed.

The Weather Project 2003

Installation view, Turbine Hall at Tate Modern

Photo: Tate Photography

© Olafur Eliasson

Typically, the most forgettable element of a visit to any given gallery, theatre or cultural landmark has been the food experience. A utilitarian cafeteria hidden away in the basement, a snack bar serving junk in the corner or even a neon-lit, fast-food outlet are the options that have been most widely available. Not limited to one particular institution, city or country, it is standard worldwide. Ironically, in the places that celebrate the beauty and diversity of our culture, food is often, at best, a mediocre afterthought, and at worst, a cynical, fast-food cash cow.

It is hard to pinpoint exactly why this has occurred. Is it a government mandate that they should aim to please all (in reality pleasing no one)? Or perhaps cash-strapped arts organisations see the promise of high returns from large, generic outfits as a way to bolster their coffers? Either way, the lack of curation by cultural institutions when it comes to catering has, however obliquely, sent the message that food experience is entirely removed from their artistic aspirations and mission of excellence.

Crucially, it now also has the effect of driving people away from spending more time in the spaces, as well as, more damagingly, telling us that food is unimportant to culture. This is a topic rarely considered, but it is one worth contemplating and one that is only now beginning to be recognised as a problem and future challenge for cultural institutions around the world.

We only need to look below the Louvre to witness how drastic the contradiction can be. Right there at the historic nexus of art and gastronomy, where once there could have been a food offering that celebrated the richness of French culture – perhaps a range from haute cuisine to democratic crepes – there is instead Starbucks and McDonald’s. The values of the institution eroded from within.

‘I wanted to plant a vegetable garden in the Tuileries,’ says Alice Waters of her ill-fated proposal in the ’90s to open a restaurant at the Louvre. It is little known, but Waters, of California’s seminal Chez Panisse, was invited to propose a restaurant in the most iconic of all iconic institutions. Her expansive vision was to create ‘a platform, an exhibit, a conservatory and a laboratory that would connect visitors to real, simple food’. It would be an installation in the form of a restaurant that breathed new life into the underutilised public space and provided a venue for patrons from all walks of life to continue the cultural conversation around the table. Put simply, she hoped the restaurant would ‘curate food like the gallery curated art’.

It was never to be, and Waters is not alone among chefs and restaurateurs whose ambitions to revolutionise food in a cultural institution have been stymied. Many have either been defeated by restrictions or seen their projects fail before they even began. ‘Arts administrators have been historically unwilling to take the same calculated risks with food that they take on their stages and on their walls’ says Waters.

Photo: Todd Selby

While their main responsibility should always be to support their art and artists first, cultural institutions are now missing an opportunity for a deeper, more meaningful engagement by not integrating food offerings that are complementary to their spaces and programming.

At this moment in time, people are craving a connection beyond the digital, and more and more we make up for that by eating in restaurants and gathering together around food. This generation of younger diners now go out for a meal like the generation before them went to the movies or to see a show. And in just about every vibrant neighbourhood in every city, the focus of life is now engaged around little restaurants, markets, coffee carts and small bars. It is a phenomenon that has been bypassing our great public spaces, but by supporting and even subsidising venues that allow for people to gather to meet, linger, contemplate, argue and dream, then the institution, and our culture, is enriched.

However, there are signs that this cultural contradiction has begun to be corrected. There are few restaurant spaces anywhere that warrant the overused description ‘iconic’, but Bennelong at the Sydney Opera House is one of them. A miniature of the larger building, the space is not only one of the prime viewing platforms of the concrete ribs, towering blades and slanted windows of Jørn Utzon’s design, but also of Sydney itself. However, it is also a room that has proven notoriously challenging for both the administrators responsible with overseeing it and the restaurateurs charged with breathing life into it.

Photo: David Prior November 2014

Early in 2014, the Sydney Opera House announced a tender process for the Bennelong space. The process divided Sydney, recriminations abounded and opinions were weighed in from every quarter. A process that was mishandled in the most public way nevertheless prompted important and, until now, rare discussion about what is indeed the role of food in a cultural institution.

Fate intervened on the first tender and forced the Sydney Opera House Board to rethink what this space could and should be. The answer was clear: a restaurant in the symbol of modern Australia, at the heart and inside the belly of its culture, should be a stage for the best of its food culture too. What will eventually go into that space is not precisely clear just now, but that the important question has been asked is an important step.

Perhaps it’s worth asking too if the often empty, glorious forecourt of Somerset House might one day play host to the best of not only the English fashion seasons, but the country’s best seasonal produce too. A weekly Somerset House Farmer’s Market? Now there is some food for thought.

David Prior