The Australian and Scandinavian landscapes could scarcely be more different. The cultures not necessarily a seamless fit either. So why then did chef Rene Redzepi make the choice relocate Noma to Sydney for a 10-week stint? The answer is both complex; an exploration of one of the food world’s final frontiers and an invigorating challenge for the world’s most lauded and referenced restaurant, and simple, who can resist a relaxing summer in Sydney?

Having followed the progress of the project over a year, and then eaten the final result, I can say that the former proved to be spot on and the latter, not quite so much. The challenges of articulating a mercurial continent, with its bizarre endemic plants, fabled no-where-else wildlife and mish-mash multi-culture, were bigger than I believe anyone at Noma originally anticipated. In other words, in order to deliver the often thought-provoking and always thoughtful ‘Australia on a plate’ (by way of Noma) there was not much time for beers by the beach. Instead of being beaten by the numerous (and often little discussed) challenges that the Australian landscape presents and offering a Noma rehash. The restaurant, so fanatical about ‘Time and Place’ as they are, embraced the daunting scale and mystery of the Australian continent and produced a singular meal that resonated powerfully with those born in the country.

Skye and I were invited by Tourism Australia to experience Noma, an opportunity we both leapt at. As ex-pats who have a particular kind of romanticism for our country it was always going to be fascinating to see another’s perspective. Unencumbered as it is by stereotypes, history and culture. From the moment we knew the project was happening we began a conversation about what is Australian food culture, where are the true strengths (and weaknesses) and challenging what we thought we knew about what it is to be from the ‘big brown land’. And there were revelations in the meal: no bread, no red, mostly wild, natives from desert to tropical, seafood and barely any meat. With the exception of seafood, these are not the elements that were accepted as the strengths.

We’re continuing the conversation below, between ourselves and perhaps a wider one has begun in Australia itself? When this Noma adventure was initially announced I oscillated between thinking it was a wildly naive venture and that perhaps that they would help allow Australians to see what was in their own backyard. In this instance the latter is the case.

Below is a dish-by-dish conversation between Skye and myself that we hope takes you through the experience in some way.

Unripe macadamia and spanner crab

Skye: First of all, what really struck me was the addition of the rose. I thought that was amazing with the crab, and surprising. And funnily enough, I’ve come back to Spring since I’ve been away and on the ice cream menu we’ve got a macadamia and rose ice cream.

David: I thought it was the unripe quality of the macadamia that was most interesting, because it has a different flavour to that kind of rich, buttery, macadamia that we know. It’s an interesting thing to start with macadamia too – macadamia being the only Australian ingredient, aside than say certain types of seafood, that has been really exportable. I thought that was a smart thing because certainly a big part of the conversation around what they are doing there is about investigating new ingredients.

Skye: Interesting to start with the crab too, and paired with the macadamia it gave a kind of snappy, sweet, almost coconut-y flavour.

David: Funnily enough, René said he felt this dish was like walking on the first frost. It’s the snap – the unripe macadamias really snapped in your mouth.

Skye: It was so pretty and feminine, almost ethereal. The rose in there gave a softness and the crab, a kind of cleanness. It was such a clean, clear, soft dish.

Wild seasonal berries flavoured with gubinge

David: The next dish, although it looked very pretty, you would never describe as feminine in terms of it’s flavour profile – that was the wild berries with gubinge.

Skye: I found it quite an unusual choice because texturally, it wasn’t a huge contrast to the first dish, but flavour-wise it couldn’t have been more different.

David: Remember the lillypilly, and muntries, and Kakadu plum in there? It was astringent, and bitter. Exactly the flavours I expected and had come accustomed to tasting Australian ingredients. Those little antioxidant hits, so small and so powerful. You just feel as if they are from the desert.

Skye: And I think the first dish was multicultural in many ways – bringing in the rose, which is very middle eastern – and then this dish was very Australian in a kind of indigenous way. You couldn’t see any cultural interference even though obviously René had stepped in.

David: It did look like a Noma dish. Berries and eathernware etc. But seeing the brilliantly bright magenta lillypilly in that dish was startling because it was lillypilly season, so all of the suburban hedges around the suburbs of Australia were full of them. Then, on the plate there were little clusters of berries that underscored an interesting aspect of the whole meal – that René and his team found the edible landscape in that very Noma way. In terms of finding the ingredients, you expect that. It was more the cultural references that I thought were interesting and fun.

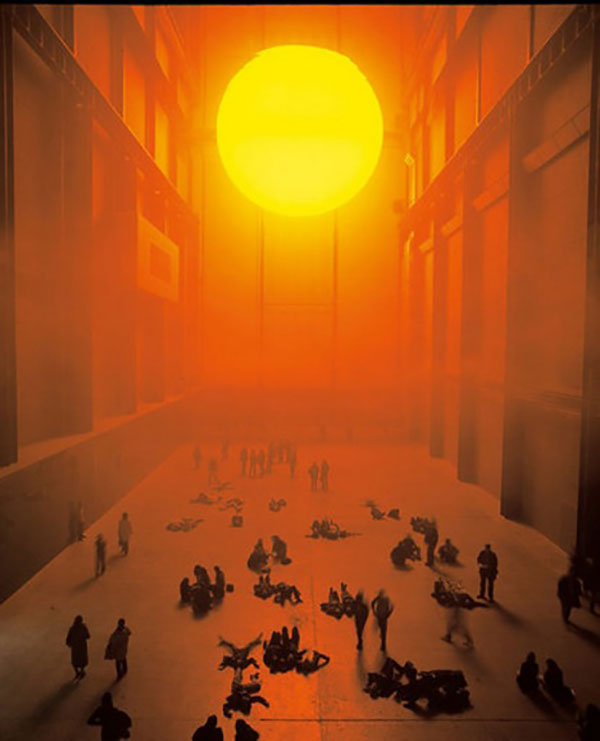

Skye: It’s the image I have of his cooking which is so firm in my mind. After the first time I went to Noma, I thought and thought about it. It was like where the sea meets the sky and there is that fine blue line where you almost can’t tell – almost like a Rothko painting – and on that line he stitches so much intricacy. They definitely hava a tone, and there is just so much complexity within that. Do you know what I mean by that?

David: I do, but I don’t agree with you – particularly with the wild berries dish. I found it the most challenging in terms of its intensity. It wasn’t easy eating in the sense of taking a bite and thinking “Oh, that’s delicious!” Instead it almost took the moisture out of your mouth in a powerful way.

Skye: The wood spoon really helped that dish as well. I adored the wood spoon with everything, it was so beautiful to put in your mouth.

David: And with the wild berries it was really effective because there’s such strong, sour notes in the berries, so you had that soft wood, which felt very nice to put in your mouth, with those powerful, astringent flavours.

Skye: That was almost where Noma met Australia so incredibly on that second dish.

Porridge of golden and desert oak wattleseed with saltbush

David: The next dish I was fascinated by. It’s the one that I thought the most about afterwards, because I kept on seeing it, and that was the porridge of golden desert oak wattleseed with saltbush.

Skye: I immediately thought these looked and kind of tasted like dolmades, but in place of an unctuous vine leaf there was saltbush and inside where there would be rice, it was full of wattleseed and a very slight acidity.

David: Wattleseed was something that I expected to see on the menu too, but this was done in a very different way.

Skye: Aesthetically, it was absolutely exquisite. The colour was faultlessly beautiful.

David: The green, the chlorophyll of those saltbush leaves was beautiful, and I think they were very young and very specifically grown. So many Australian ingredients are foraged or found, or have unreliable lines of ordering for restaurants so it can be really challenging. If you have saltbush that’s a little older, it would be really intense, too intense frankly, but, the saltbush at Noma was just vaguely salty. I’m so interested to see if the market opens up for an ingredient like that.

Skye: It was very mellow and balanced.

David: It reminded me of the ants in North Queensland that stitch a leaf together to make their home and protect themselves from torrential downpours. The little wattle seeds looked like ants in there. For me, that touched a Queensland note. Does that sound bizarre?

Skye: I thought that was beautifully placed within the composition of the whole meal. It really cleansed the palate before the seafood platter and crocodile fat, which was such a rich dish.

Seafood platter and crocodile fat

David: There was a lot on the plate for this one. Five or six kinds of mollusks – pippies, strawberry clams, those big, fleshy oysters – and then the crocodile fat over it.

Skye: The crocodile fat gave it a musty, almost Marmitey flavour. It was the most confronting of all the dishes, to me.

David: I’ve eaten crocodile a couple of times, and it seems to be the ultimate challenge to make it delicious and for me, it has never truly been that. It’s interesting that they paired it with the seafood, which is probably the most accessible side of Australian ingredients. The vast majority of Australians would not be confronted by eating an oyster, a pippie, a clam, but with the crocodile fat on it, it takes it to a different place; whereas the next dish was really about leaving the product alone. My friend called it Lardo di Kakadu, which I thought was hilarious.

WA deep-sea snow crab with cured egg yolk

Skye: The snow crab with cured egg yolk was such an elegant dish.

David: It was extraordinary. It was a mound of the most beautiful picked snow crab from Western Australian, then very vaguely enriched by cured egg yolk.

Skye: You just put it in your mouth and it was a complete sense of pleasure and satisfaction. I found it so round, so full, and yet so balanced and restrained at the same time.

David: With the note of kangaroo in there and fermented egg yolk, it really felt like it was the richest, most indulgent crab you’d ever tasted.

Pie: dried scallops and lantana flowers

David: The next one was the pie with dried scallops.

Skye: For me there was a real reference to urban Australia here. Meat pies were an Australian institution, certainly in the ’70s, and even early ’80s, and lantana was in everybody’s back garden, and is actually poisonous but has a very beautiful flower.

David: The lantana threw me at first, because it just has such resonance, a particular generation hate that plant – it’s like poison ivy in your back garden, but it is actually very beautiful. I think it was an ingredient, along with the crocodile, that was included to provoke thought; and certainly they did but will I crave lantana, no.

BBQ’d milk “dumpling”, marron and magpie goose

Skye: I thought the next dish was extraordinarily successful – the barbecued milk dumpling.

David: It was almost like an Australian taco.

Skye: That was burned milk, the skin. To me, that felt very Scandinavian – an influence from that part of the world.

David: But, the taste for me was all about the the rich meat – the maron meat, which is so delicious, and then I didn’t get so much of the magpie goose, but there was a meatiness in there too.

Sea urchin and tomato dried with pepperberries

Skye: Then we had the breather, with the sea urchin with the barely dried tomatoes from Tasmania, and the pepperberries that were very sweet, almost like soft blankets. It was an incredibly, rich yet gentle dish.

David: It was so intensely flavored and beautiful.

Skye: And another one without too much interference, that took indigenous ingredients and let you see what they can do on their own.

Abalone schnitzel and bush condiments

David: Then there was something that I really loved about the abalone schnitzel, with that half torpedo of finger lime.

Skye: The abalone was deliciously tender, it came piping hot, which I adored – schnitzel should always be served hot. It might have even been one of the most delicious dishes on the menu, but it didn’t get me thinking like some of the others.

David: It was like the ultimate schnitzel. I thought it was a really fun moment. This was more a dish that you just enjoyed, and I think that’s great. What about all the other condiments?

Skye: There was a charming irony to that dish.

Rum lamington

David: The other ironic dish – and we knew there would be something along these lines – was the rum lamington. But for me it was too boozy.

Skye: That was probably the hardest dish, because they probably felt, for so many reasons, they had to include it, and yet you can’t really improve on it.

David: Lamingtons are so iconic in Australia, they’re like the Sydney Opera House of food.

Skye: I actually always think of mangos as something that is so Australian to me, which was gorgeous in the marinated fruit.

Marinated fresh fruit

David: It was almost like a fruit platter, and the mango was almost over-ripe. Then in order to get that mango slightly underipe tang back, they used the green ants, which have that explosion of acidic quality, which was briliant.

Skye: Also the watermelon was kind of compressed, so it tasted like a watermelon, but it didn’t quite have the texture.

Peanut milk and freekeh “Baytime”

David: What about the “Baytime”? When I first bit into it, it had the same sensation as a really healthful dessert, something from one of those Paleo cafes. And naturally I wasn’t so sure about it but then I mulled on it for a second and wanted more. Then I couldn’t stop.

Skye: I’ve thought about that dish for ages, and the brilliance of taking burnt freekah, which is just on the border of what bitter chocolate could be, in terms of smokiness. Then the kind of nuttiness of the peanut ice cream, which became more intense, more rich in the centre. It was an elegant dish – not sweet, yet a completely satisfying dessert. I think it finished the meal off so beautifully. It was a perfect combination between Noma and Australia, the two cultures meeting.

The Noma Australia experience

Skye: Do you remember we talked so much before about where Noma would end and Australia begin? In the end, you couldn’t separate it, could you?

David: No. When you have such a point of view, it becomes Noma’s take on Australia. It’s not “here is Australia on a plate.” It’s “here is Australia by way of Copenhagen”. Some of it can always seem slightly lost in translation but it wasn’t earnestness, it was fun and so that made it all the more endearing.

Skye: It was so unforced. There was nothing serious about the meal for me. It was like the best of any meal, not just on deliciousness, but the whole thought made me smile.

David: I really like that René said honestly to me that part of the reason he wanted to go to Australia was so his kids could have an Australian summer and to get away from the cold for a bit. In some ways, it’s a very Australian thing to be so honest about that. Other people would say, “I’m going because it’s the next food frontier.” Of course, that’s part of the reason, but it’s not the only one and that’s what made it sophisticated. It was fun; they weren’t trying to sell an agenda. It felt very celebratory.

Skye: They weren’t looking for the next great accolade – it didn’t feel like that kind of meal. There’s a real confidence in that.

David: An extension on that point, is that the Noma service style is a very Scandinavian kind of open-faced, happy service, which is very Australian as well. They’re very unpretentious, they’re very welcoming. It’s not a kind of helicopter, obsequious service. It’s casual, but professional and proud.

Skye: The other thing that was amazing about that service, which I kept thinking about after we left, was how energized it was. I loved the food, but it’s like when I went to Noma the first time, I just loved being there. I loved the energy. The whole experience made me feel happy.

David: There’s definitely something within the Noma family, a sort of mode that they work in internally and externally.

kye: They bring it onto the floor in such a wonderful way. It almost felt like an extended fun dinner party. That was maybe the most Australian aspect of all.